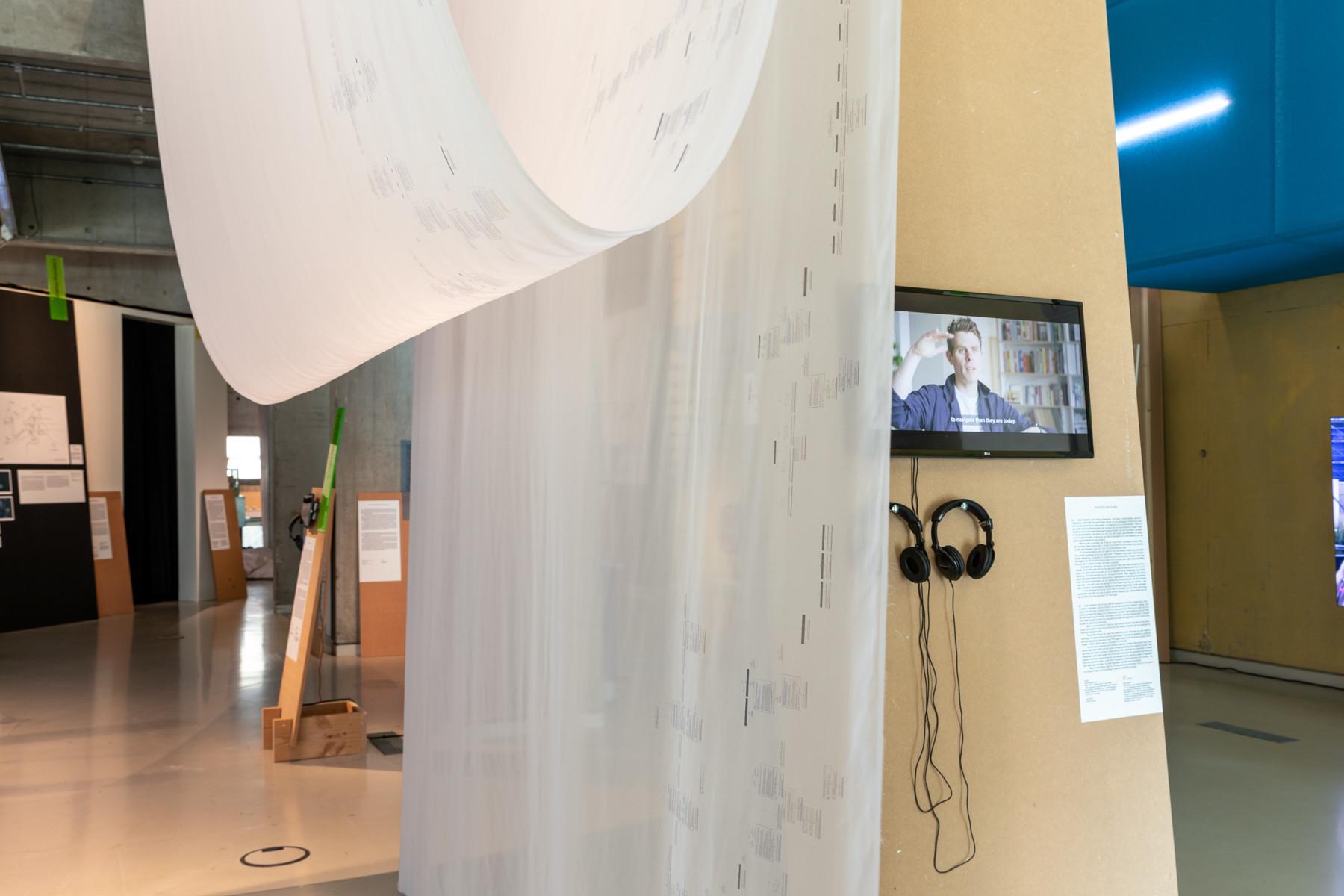

Nature of Hope approaches architecture as an ecological practice. People are not separate from nature, but an integral part of it. But the binary thinking in which nature is everything that is not human or made by people has a long and dominant history. To introduce the exhibition, IABR therefore asked researchers, philosophers, historians and writers to reflect on how we look at nature. Every week we share one of the contributions, which can also be seen in the exhibition.

Matthew Gandy explores how a grapevine, a plant that sprang up everywhere on wastelands in post-war Berlin, changed the way Berlin ecologists viewed nature.

While working in the library of the Institute of Ecology at Berlin’s Technical University in early 2013, I happened to notice a metal filing cabinet by the window. My curiosity got the better of me and I opened one of the drawers to find neat rows of 35mm slides depicting the plants of Berlin that had been used for teaching purposes. The mounts for each slide had a series of neat handwritten inscriptions, revealing that most of the photographs dated from fieldwork carried out in the 1960s and 1970s. One of the most striking images, taken by botanist Ursula Hennig in 1968, depicts a plant known as sticky goosefoot (Dysphania botrys) growing on a wasteland in the former island city of West Berlin, near to what is now Potsdamerplatz. There is something magical about a color transparency with its saturated colors and hyperreal depth of field. We can imagine walking into the frame to take a closer look. Our eye is drawn to a yellow ruler jutting out of the ground, an artfully placed piece of scientific equipment at the center of the composition. This distinctive and highly fragrant plant, originally from the Mediterranean, had spread rapidly on rubble-strewn sites in the wake of war-time destruction. For Berlin’s ecologists Dysphania botrys had become a signature species for the study of so-called Brachen, or empty sites, that were a focus of intense cultural and scientific interest in the post-war period. In 1971, for instance, a botanical journal even published a special issue devoted to this species alone. Dysphania botrys is a distinctive element in the emergence of ‘cosmopolitan ecologies’ that comprise species from all over the world. For the Berlin-based urban botanists a fascination with unusual biotopes also marked a challenge to the earlier emphasis on ‘native ecologies’ within vegetation science that had spilled over into xenophobic anxieties. Here was a new kind of urban ecology that celebrated the complexity of urban nature, including multiple traces of global history to be discovered on every street corner. In recent years Dysphania botrys has become much scarcer in Berlin: most of the former Brachen or wastelands have been built over.

When I tried to find the plant in the summer of 2015, during the filming of my documentary film Natura Urbana: the Brachen of Berlin, I only managed to encounter the species by chance in a car park with the help of botanist Birgit Seitz from Berlin’s Technical University. It is ironic perhaps that while most of the original botanical wonderlands associated with ruderal ecologies have gone, we now encounter the staging of a Brachen aesthetic within a number of prize-winning designs for new parks in the city where ecology, memory, and public space have been combined to produce a visual tableau that preserves these unusual aspects of urban history.