Nature of Hope approaches architecture as an ecological practice. People are not separate from nature, but an integral part of it. But the binary thinking in which nature is everything that is not human or made by people has a long and dominant history. To introduce the exhibition, IABR therefore asked researchers, philosophers, historians and writers to reflect on how we look at nature. Every week we share one of the contributions, which can also be seen in the exhibition.

Marinke Steenhuis takes us to the cause of dualistic thinking in the Dutch cultural landscape.

For centuries, the sandy soils of northwestern Europe were subject to a clear order of land use. The manure used on the ashes was produced by the sheep on the collective agricultural heath. The united organization of farmers was called the marke; its members helped each other bring in the harvest and performed neighborly duties in the case of births, illness, death, and natural disasters. The agricultural system was restrictive; water and soil were guiding, every part of the cultural landscape was used. The concept of nature did not exist.

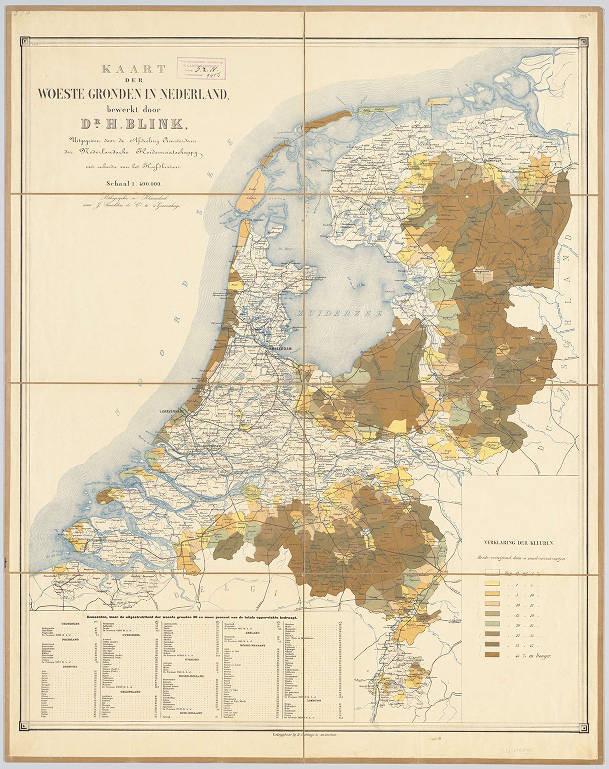

From 1850, this balance changed completely. The poor sandy soils had to be made more profitable and be distributed, an idea that finally found a legal basis in the Marke Laws of 1886. Farmers organized the distribution in the marke itself. Wealthy families and newly founded nature organizations from the cities bought large parts of the heaths to plant forests and establish estates that enjoyed tax advantages under the 1928 Natuurschoonwet (Natural Beauty Act). The Veluwe, the Sallandse Heuvelrug, the Oisterwijkse forests and fens, or the Goois Nature Reserve: they are all former collective properties of farmers. In the public perception of around 1900, these areas went from desolate to valuable; the socially acceptable paintings of the Hague School reinforced this image. The policy category of a ‘nature’ that had to be preserved, was born.

For a century and a half, the imperative of physical and political growth has applied to both agricultural and conservation policy. In farming communities, the sense of loss of control over the integral agricultural cultural landscape is still strong. Farmers feel alienated from their own, once collective land and work ‘around nature reserves.’ Nature organizations, on the other hand, think in terms of natural areas and are concerned about the loss of biodiversity. This is the historical explanation for the harmful polarization between agriculture and nature.

In the area-specific approach developed by SteenhuisMeurs, the system and living worlds are brought together from a variety of (archival) sources and conversations with agricultural and nature parties. Awareness of the essential mechanisms and characteristics of an area changes the relationship between farmers, officials, and nature conservationists. Stagnation and mistrust give way to recognition, pride, and understanding – resulting in a tremendous softening of the process. The area-specific process is the key to a new future – respecting each other’s origins, time horizons, and historical connections.