With more than 70 architects, researchers, designers, and writers, Nature of Hope offers a wealth of perspectives and ideas on how architecture and spatial design can contribute to regenerating nature, biodiversity, and restoring ecological balance. But what is really needed for a more hopeful, regenerative design practice? How are ambitious visions sown and harvested in the international architectural landscape?

All the way from Colombia, Pedro Aparicio-Llorente, architect and founding principal of APLO (acronym for aligning planets lines orbits), an architecture and landscape firm based in Bogotá that makes and researches buildings and landscapes, came to speak at the symposium this weekend. His work stems from 10 years of experience in design and construction within the material practices and political ecologies of postcolonial tropical habitats. Pedro holds an architecture degree from Universidad de los Andes and an MDes in Urbanism, Landscape, Ecology from Harvard University Graduate School of Design. We briefly spoke with Pedro about his vision on architecture, his reflections on the biennale's theme, and the work that is on display.

The environment shapes architecture

Firstly, Pedro takes us through his approach to architecture, which centers on cohabitation and experimental ways of living together. "I have learned to let the environment shape us, rather than us shaping the environment. The environment informs architecture in many ways, especially in biodiverse regions like the Gulf of Tribugá, where the rhythms of the pacific ocean, mangroves, and jungle organize space itself." In more northern countries, this way of thinking is less common—we tend to build with whatever is demanded and with resources that are available. Pedro and his colleagues at APLO adopt a more humble and context-sensitive approach. "We design with the understanding that everything is alive. For example, how can a mangrove forest, which floods and dries out every six hours, inform architectural design? We used contemporary architectural methods and allowed the behavior of marine ecosystems and the technologies devised and used by local people to guide the further design. This philosophy underpins my work and is showcased at the biennale."

What makes Pedro’s and his team's view unique is his interest in landscape as a live medium within a cultural context where landscape architecture is not recognized. "In Colombia, landscape architecture is not a discipline in the same way it is in the Anglo-Saxon context for example, yet we live amidst tropical ecosystems where the interaction and manipulation of live media is an everyday practice and this is then our entry point to explore space and time." Pedro explains. His previous work in Indonesia exposed him to dynamic environments where volcanoes and obsolete yet operational colonial infrastructures meet. "These habitats connect people deeply to the complexity of somewhat mestizo ecologies—from practical, productive ways of growing food to highly spiritual levels of transmission. This creates a continuum that is fertile and fascinating to consider in terms of contextual and situated architecture, leading to a more expanded notion of whom we design for, for what purpose, and how the environment shapes us as a species. In this matter, as architects we are interested in the turn towards a design of time, rather than a limited practice focused mostly on the design of space."

Veanvé: Environmental Infrastructure for Pluriversal Pedagogy

For this way of working as an architect, one needs knowledge - very specific and locally sourced knowledge on how nature and people shape the environment. On show in the biennale are three processes carried out by APLO that give insights in the approach they advocate for: Veanvé, an environmental infrastructure for pluriversal pedagogy and planetary ocean health; Payao, the use and evolution of an old fishing technology that originated in the Philippines and made its way to the artisanal fishing group Tiburones de Coquí around 10 years ago and; Jurubirá, a still incipient landscape plan for community based tourism.

During the symposium, Pedro walks us through the ways of feeling-doing that APLO applies with communities that live in specific ecosystems and how to build from there. One of the projects Pedro discussed is Veanvé, an environmental infrastructure for pluriversal pedagogy and planetary ocean health. In alliance with local leader Josefina Klinger and the Mano Cambiada Corporation, the Center aims to safeguard the traditional knowledge and ecosystems of Colombia's Tribugá Gulf, which was designated as a Hope Spot in 2019 due to its significant contribution to oceanic well-being, making it one of the most biologically diverse regions in the world. Recently, the gulf was declared a Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO for being one of the few ecosystems in the world that is in balance.

Veanvé brings to life the evolution of the Pacific Migration Festival, transforming it from an event-based strategy, initiated by the local organization Mano Cambiada in 2010, into a dynamic and educational infrastructure. Each year, the Festival gathers 1,000 young participants, immersing them in a blend of scientific, sporting, and cultural activities. These experiences celebrate the region's unique status as a sanctuary where humpback whales travel thousands of kilometers from Antarctica to the warm and deep waters of Colombia to give birth. This narrative redefines Tribugá, shifting the perception from a place of violence and hopelessness to one of love and vitality. Guided to envision themselves as waves, birds, turtles, whales, and other elements of their surrounding ecology, they explore the interconnectedness of their environment, learning to appreciate the delicate balance that sustains their home. Finally the building is imagined to happen in the abandoned Telecom station, a public infrastructure that first served the community in terms of telegraph, telephone and internet connection prior to the arrival of mobile phones. Charged with collective memory, this building is now owned by the spanish telecommunication conglomerate Telefonica who bought Colombia’s public communication enterprise in the early 2000’s. Pedro underlines that hopefully an agreement can be settled for it to be transformed into a collective space once again.

Hope as a place and projection

This brings us to the theme of the biennale, Nature Of Hope. Reflecting on this, Pedro explains, "Why is a place thought dangerous by humans the place chosen by whales to have their babies? Everyone wants to travel the world and seek opportunities, but true hope is rooted in generational care, passing on the responsibility of a specific place. This perspective is hopeful in itself—there is much more than we are aware of and often “closer to home”. It flips the notion of possibility of every place we work with if we learn to view it from a more socio-environmental perspective." Veanvé is a place to experiment with ways for generational relief by equipping children and youth with tools that contribute to their territorial inheritance of caretaking over 200,000 hectares of collective land inhabited by some of the world's most sensitive ecosystems: mangroves, coral reefs and rainforests.

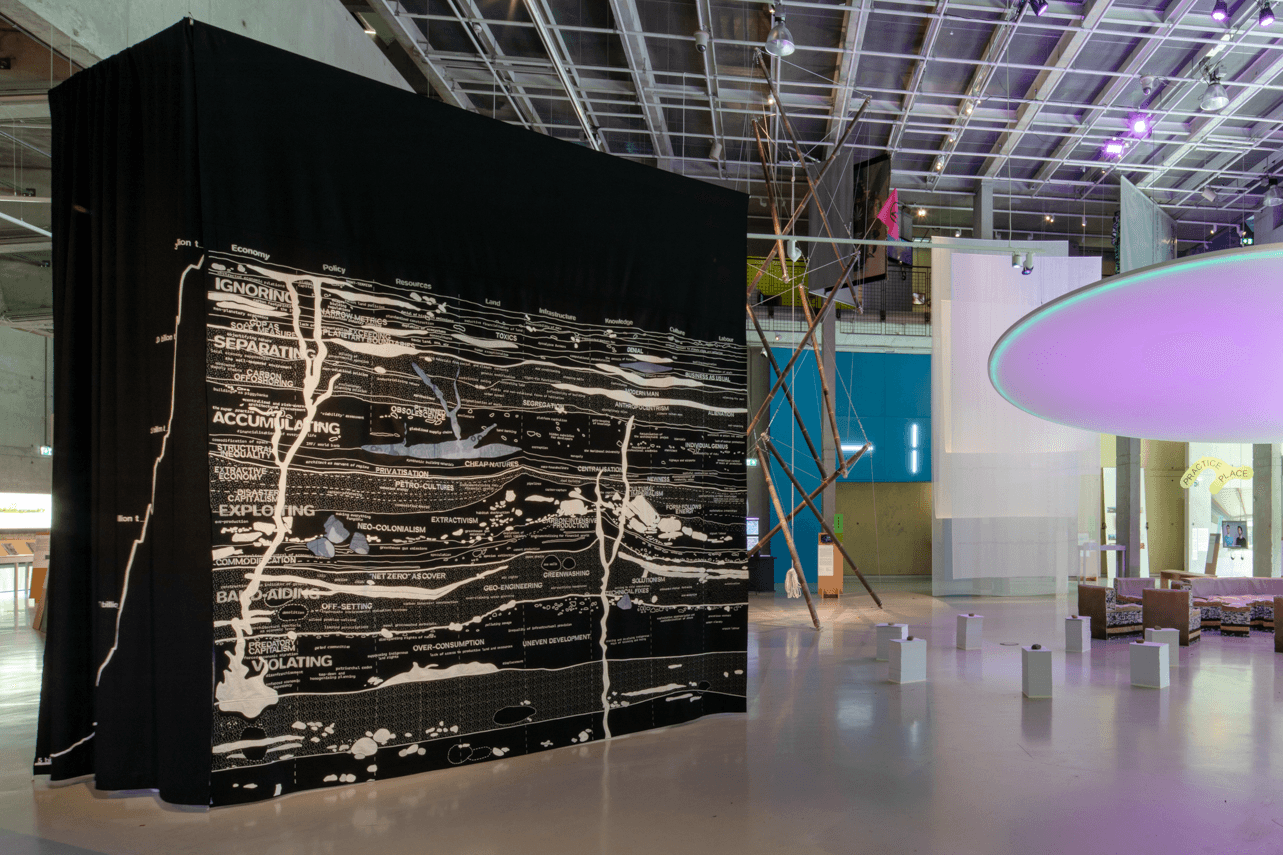

Much like the annual migration of species returning to the same place, as celebrated during the Pacific Migration Festival, where hope is intertwined with the well-being of the place, Pedro sees hope as a projection—looking forward to something, traveling, or working towards a goal. Not in a way that the future has to be idealized; rather, Pedro's vision focuses on speculating on a transformed present rather than simply hoping for a better future. "These are not projects of 5 years; they are processes of 30 or 40 years. My personal hope is that, as architects, we can accompany these existing flows, finding new ways to design companionship and by doing so, prepare ourselves and our work for long term causes." To learn about how to do that, you are welcome to visit Nieuwe Instituut, where the work of APLO is exhibited.