With more than 70 architects, researchers, designers, and writers, Nature of Hope offers a wealth of perspectives and ideas on how architecture and spatial design can contribute to regenerating nature, biodiversity, and restoring ecological balance. But what is really needed for a more hopeful, regenerative design practice? How are ambitious visions sown and harvested in the international architectural landscape?

One of the speakers who shared his insights during the IABR symposium last weekend, came by bike all the way from Britain, leaving no ecological footprint. This was Jeremy Till, a British architect, educator, and writer, and Professor of Architecture at Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London, representing the collective MOULD. We briefly spoke to him about the research collective MOULD, the work showcased at the biennale, and his vision for the discipline.

Research Collective MOULD

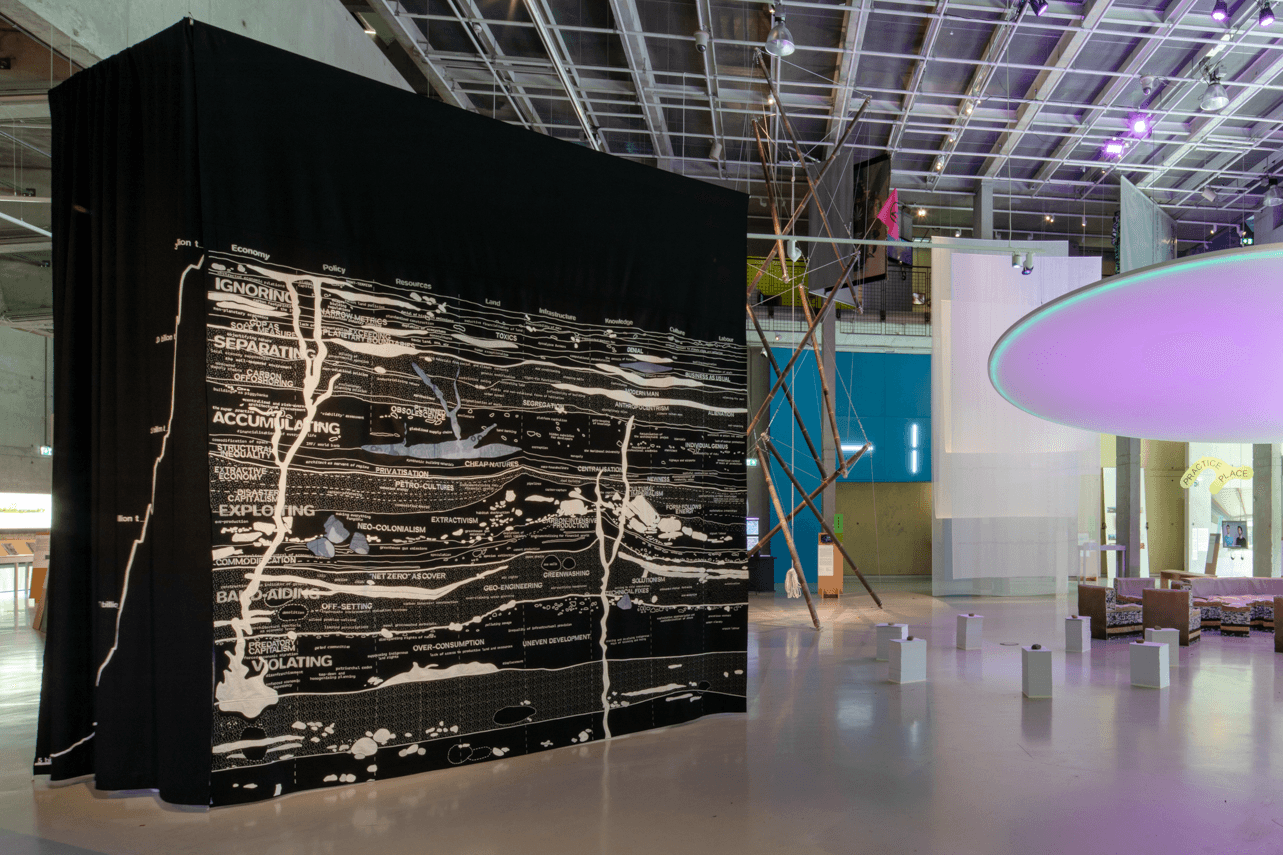

First and foremost, Till makes it clear that he is not here as Jeremy Till, but as part of the collective MOULD, which he is part of with five other colleagues. They share the vision he wants to convey in this interview. MOULD is a research collective working at the intersection of spatial practice and climate change. The work of MOULD, "Architecture is Climate," currently showcased in de Nieuwe Instituut as part of the biennial, reflects the collective’s deep commitment to addressing the urgent challenges posed by climate change. MOULD’s work embodies a collaborative, interdisciplinary approach to architectural practice, with a vision rooted in deep political and ethical concerns about the world. The collective has mapped out various practices—not as architecture as we know it, but examples from different regions, contexts, and disciplines that directly address climate change and its spatial implications. They strive to think differently about architecture, not just as the design of buildings, but as a practice informed by diverse forms of knowledge and culture.

Architecture and Climate

MOULD’s work at the biennale, a large installation, reflects these insights and emphasizes the vision that architecture is not separate from the climate; on the contrary, it is deeply intertwined with it. The project underscores that traditional architectural practices are complicit in the causes of climate change. Till explains: "The installation shows that viewing architecture as an external solution is like applying a band-aid to a much larger wound. Instead, we advocate for an upstream approach, addressing the root causes of climate problems much more directly and locally."

Underlying their work is a significant critique of current architectural practice: the trend of "sustainable" or "green" architecture, which Till sees too often as a form of greenwashing. He argues that many technical solutions to achieve net-zero emissions are potentially counterproductive if they enable continuous growth and consumption. These solutions, while necessary, must be accompanied by systemic changes. As Till succinctly puts it:

"The most dangerous is the technical solutions - we need them, of course. But the biggest solutions allow endless growth. On the one hand, you can have a solution to get to net zero, that is a technical solution, but then we continue to extract and consume. That will remain damaging because it will be accompanied by growth which is always accompanied by extractive practices that damage the planet. One has to be quite careful about not privileging the world of architecture too much. We are part of a network of solidarity, which is bound into to politics, economics, and society. We have defined ourselves as a discipline that provides solutions. But that might be too arrogant, to say that architecture is generative. Designers tend to look just downstream, see a wonderful future, reinvent the world. But you first need to look upstream. You need to look at the causes of climate breakdown and address them first. Only then can it be sustainable."

It is clear: Till advocates for a more realistic view of architecture that is closer to what is actually happening and what the problems are in each local practice. Environmental problems must be examined in context. That is the only sustainable way to build to prevent ecological collapse, which requires reinvented forms of architecture. "We cannot afford repetitions of the same architectural solutions and must better address specific challenges. From policy solutions to diverse methods of land use, to the use of different resources. This requires a broader view from our discipline", shares Till.

Hopeful Future

Despite the challenges, Till remains hopeful. He believes that the necessary systemic changes driven by climate demands will lead to broader social transformations. These transformations will manifest spatially, as social relationships inherently play out in space. This perspective shifts the role of architects from mere builders to spatial designers and agents who use spatial intelligence within a broader context of social change.

This is why Till looks forward to the other works on display during the biennale with enthusiasm. "What is encouraging is the diversity of architectural approaches seen here—it shows that they already exist. Architects have historically always identified themselves through their buildings. The past few years have shown how difficult it is for architects to let go of that and recognize that architecture is about much more than just the object and the materials it is made of.. At this biennale, you see that architects dare to identify with other methods. Methods that may still be invisible, not yet visible in the field or iconic architecture magazines, but that will ultimately make a difference."

MOULD’s participation in the biennale marks a crucial shift in architectural thinking. Till shared his insights during the IABR symposium on June 30—the work of MOULD is on display in the exhibition. Visit the website for information about curator-led tours for more context on the work.