After Airspace, Data Hazard contributes to a larger study about the social and spatial implications from introducing passenger and freight drones into the European Union. Within the EU drones are described as “new aviation.” This title has its basis in European Commission policy (EC, 2014) and importantly reveals the constellation of expertise that has jurisdiction over designing urban space for drones. Aviation’s traditional scope of concern is national because countries’ have sovereign control over their airspace, and simultaneously planetary, the outcome of more than eighty years of transnational institution building. However, drones act at the scale of front- or back-yards, rooftops, warehouses, hospitals; they traverse streets, districts, infrastructural corridors and cities as well as extended urban regions. From the perspective of architecture and urbanism this presents a set of questions. How does aviation expertise view and understand the city and extended urban regions and what conceptual frameworks, tools, or formal techniques does it apply in the design of urban space for drones? Because this presents a large field of inquiry, After Airspace, Data Hazard focuses on one aspect, the use of digital protocols for designing urban airspace.

Research

After Airspace, Data Hazard: Drafting Algorithms for European City Skies

Agent of Change - Simon Rabyniuk

2024 – 2025

Research by

- Simon Rabyniuk

- Credits

After Airspace, Data Hazard developed through interviews with regulators, researchers and private enterprise who participate in creating Europe as a drone ecosystem. While the most common definition of the term drone ecosystem implies a network of business partnerships, After Airspace, Data Hazard asserts an expanded view, by interpreting the spatial effects of drone protocols.

Through interviews I’ve encountered a narrow centralization of expertise within aviation. The network of actors includes EU governance bodies and agencies. Individual Member-States are also developing their own positions on drones. In the Netherlands the national government, airspace regulator, aviation research agency, as well as select provinces and municipalities have created agencies, teams, and startup-like entities. These groups provide more than just regulatory and research capacity for this issue and are acting as drone advocates. Of course, legacy aviation companies and drone startups are also present. Because of the history of industrial policy in Europe, much EU drone research happens through trans-European partnerships that include government, academy, and private industry: it isn’t possible to draw a boundary between the public and private.

Further background information about After Airspace, Data Hazard

After Airspace, Data Hazard interprets EU research creating algorithms for managing swarms of drones. While passenger and freight drones aren’t yet flying en masse; these projects participate in the incremental development of the rules, standards, technologies and institutions that might one-day achieve this infrastructural transformation.

The visual essay use analogies from urbanism, that of zoning, setbacks, traffic organization and the design of traffic structures. This translates the spatial effects of drone protocols into a language familiar for an urban minded audience. This presents an invitation for people to engage with the larger process of introducing drones in the EU in the role of urban advocate.

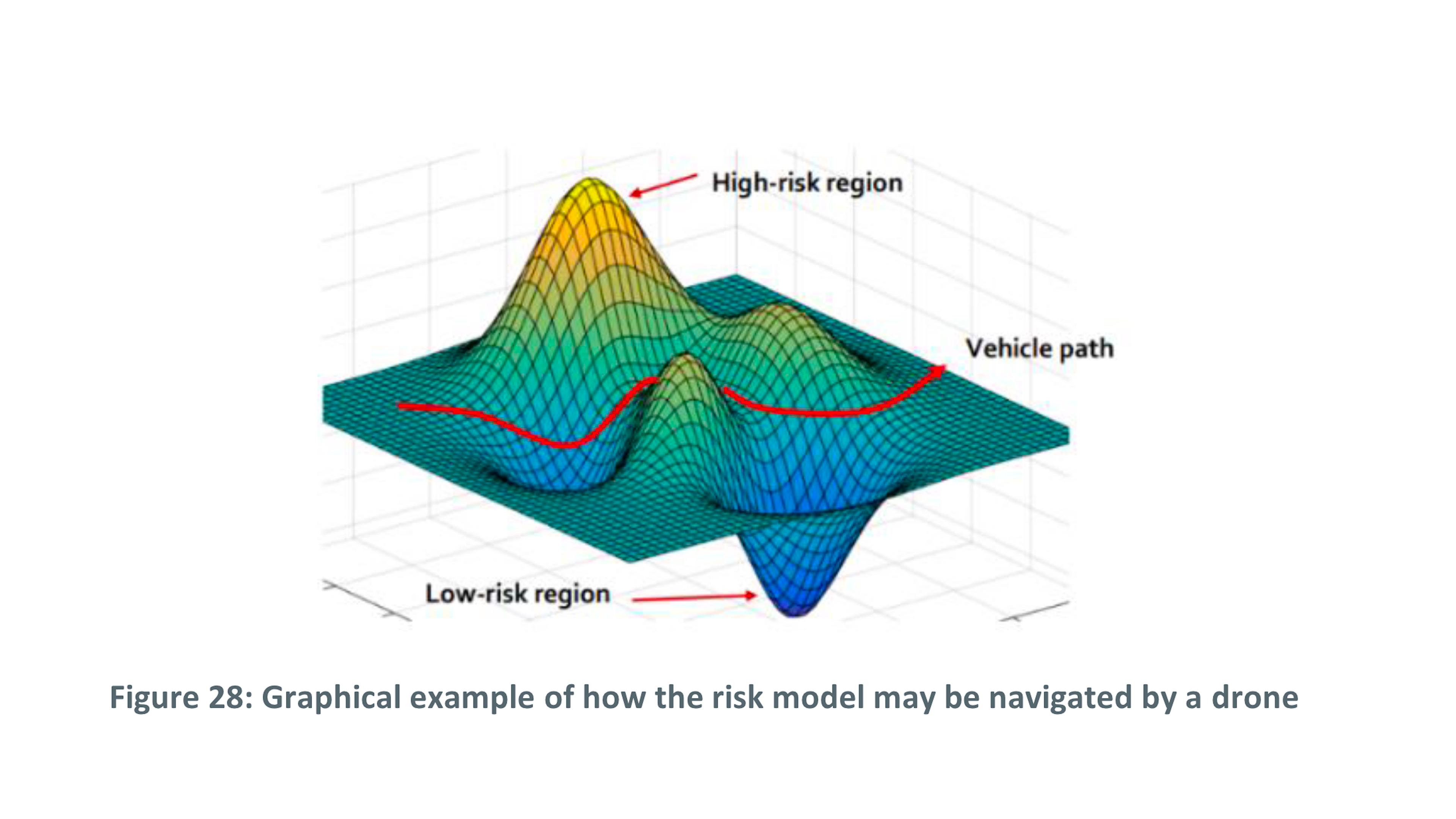

Two high-level findings from the research include: EU drone protocols are redesigning the form and performance of cities. They do so by reclassifying large volumes of space for drones, by deciding how densely drones can pack the sky, by creating formal structures that organize how drones move through urban airspace, as well as by planning high volume corridors. EU researchers test different scenarios. They evaluate scenarios based on which ones enable high volume operations.

Second, Aviation expertise has limited tools for describing urban space. Because of this, existing practices from international aviation taken from 6000+ m’s in the air, as well as how urban simulators structure information, influence the design of each scenario. This leads to the city sky being treated as if it were separate from cities. This leads to the design of drone protocols that standardize dramatically different urban conditions. It also prevents any interaction between the design of urban airspace and existing (or projective) terrestrial planning.

An urban advocate might approach the design of drone protocols through values of urban ecological stewardship, the creation of rich public spaces, or design for social interaction. An urban advocate might also seek to understand how the design of urban airspace supports future city or regional aims; however, that simply isn’t yet happening.

In parallel with the video essay, I’ve written a chapter length discussion of the algorithmic governance of EU urban airspace for drones. My doctoral project is called Single European Sky: The Architecture of U-space and is undertaken within the chair of Architectural History / Theory at Eindhoven University of Technology. The project traces the different elements that are constructing Europe as a drone ecosystem. These include its institutions, algorithms, test beds and physical infrastructure.

What is the research method of After Airspace, Data Hazard?

This project uses two research methods. The first is a close reading of EU-funded drone research reports published between 2017 and 2022. While this period encompasses the work of more than twenty-nine trans-European drone research consortia, After Airspace, Data Hazard focuses on five projects. Their official titles are CORUS, BUBBLES, METROPOLIS 2, DACUS, USEPE. Each consortia included governmental, academic and private actors. These projects were chosen because they each tested digital protocols for managing the simultaneous flight of drones in cities, they each employed urban simulation to test the effects of their protocols in an urban environment and their protocols mimicked the practices of zoning, setbacks, traffic organization or the design traffic structures. Project reports include urban diagrams that visualize how the protocols manipulate urban space. Visual analysis of these diagrams provided key insight. The second method involved interviewing a cross-section of people who led these drone research projects or who were more broadly participate in the Dutch drone ecosystem. Interviews revealed insight about the process of realizing each project. This often-included personal reflections about the nature of the work that wasn’t documented in the formal reporting.

What do we hope to accomplish with this research?

I asked an aviation expert leading an EU drone research project if anyone within their consortia served as an urban advocate? I broadly defined the role as someone who might interpret the work from the ground up rather than sky down. While hardly the state-of-the-art in urbanism, this could be as simple as reflecting on how drones impact the experience of the public realm or the quality of social interaction between people. Self-reflectively pausing, this world-class researcher replied “no;” even these basic ideas about how to design urban space fell outside the project’s frame of reference.

By critically discussing aviation expertise’s expanded jurisdiction –that of the city– After Airspace, Data Hazard, and the larger doctoral project, reveal the spatial logics and institutional priorities advancing drones in Europe. By translating concepts and practices back-and-forth between aviation and urbanism the project aims to foster unlikely alliances between air minded and urban minded expertise that might redirect the drone’s current inertia.